Unmanned Aerial Vehicles -- drone aircraft -- grow more sophisticated and cheaper every day. The Obama Administration has amply proved their effectiveness as weapons, and drones continue to kill people in Yemen and Pakistan almost every week. The political and social impact of those strikes is changing the nature of the conflict in Afghanistan, with consequences military officials can not foresee with any accuracy.

As always, such developments have spread beyond their original use. Law enforcement and counterintelligence types now look forward to the day when they can fly drones in US skies to keep an eye on what's happening in this country. This blog has discussed this possibility before, but the Times considered it again this week.

It's not obvious how drone surveillance fits into current American law. The US Supreme Court recently heard arguments about the use of drug-sniffing dogs, and the way it rules there may indicate how the current justices think about the concept of privacy. The drafters of the 4th Amendment did not envision the government looking at our "persons, papers and effects," and it';s not clear how drone surveillance would affect how "secure" we are in those things, anyway. Police drive back and forth along city streets all the time, and that is not considered an invasion of privacy; if they watching from much farther away but with much better cameras, might that not be simply a more effective way of doing the same thing? Still, the idea is creepy.

But the main point is that once again life has outstripped law. Obama wants rules in place, and that's a start, but Congress and the courts need to get to work, too.

Monday, December 31, 2012

Tuesday, December 18, 2012

No Words

I have said before that I can not understand the position of gun-ownership advocates like the NRA. But no gun control proposal short of banning all guns could have prevented the massacre at Newtown, Connecticut on Friday. The woman who owned the guns would have passed every check. The guns themselves do not, I believe, qualify as assault weapons, so even the proposed limits on certain firearms would not help.

NRA-type arguments that her gun possession could have protected her are nonsense, since she was not going to shoot her son as he drove up to her house. And I hope no one is suggesting that we arm teachers at elementary schools.

This is one we just have to swallow. As a father of young children and an uncle of two girls who were in school 20 minutes from Newtown, the story is beyond painful. But let's not pretend it can be fixed.

NRA-type arguments that her gun possession could have protected her are nonsense, since she was not going to shoot her son as he drove up to her house. And I hope no one is suggesting that we arm teachers at elementary schools.

This is one we just have to swallow. As a father of young children and an uncle of two girls who were in school 20 minutes from Newtown, the story is beyond painful. But let's not pretend it can be fixed.

Sunday, December 9, 2012

Is This a Republican Form of Government?

The United States Constitution guarantees to each state a "republican form of government." Nowhere does it explain exactly what that means, but we can assume a few things and the Supreme Court has announced a few others.

First, government must be chosen through democratic elections. For no good reason, the US Supreme Court has said that state legislatures, unlike the federal one, must include two houses both of which are directly elected. It also has created a series of rules about the way election districts can be drawn. (see Reynolds v. Sims)

Second, there ought to be some level of transparency and the rule of law. People ought to be able to understand what the law says and how it was written

By this second standard, the state of New York is like a bizarrely wealthy and high-developed political backwater. For the last few weeks, Albany insiders have been railing on about the way state senate leadership will affect jobs, the economy, minorities and a bunch of other stuff. But I can not find a single explanation for why the back-room dealings a few members of the smaller house of the state legislature should entirely determine the agenda for the government for the next term. How are these decisions made? Once they are made, how do they coerce the rest of the membership to do what they are told?

I have been trying -- admittedly not that hard -- to figure this stuff out for a while, and I can't. But shouldn't it be obvious?

First, government must be chosen through democratic elections. For no good reason, the US Supreme Court has said that state legislatures, unlike the federal one, must include two houses both of which are directly elected. It also has created a series of rules about the way election districts can be drawn. (see Reynolds v. Sims)

Second, there ought to be some level of transparency and the rule of law. People ought to be able to understand what the law says and how it was written

By this second standard, the state of New York is like a bizarrely wealthy and high-developed political backwater. For the last few weeks, Albany insiders have been railing on about the way state senate leadership will affect jobs, the economy, minorities and a bunch of other stuff. But I can not find a single explanation for why the back-room dealings a few members of the smaller house of the state legislature should entirely determine the agenda for the government for the next term. How are these decisions made? Once they are made, how do they coerce the rest of the membership to do what they are told?

I have been trying -- admittedly not that hard -- to figure this stuff out for a while, and I can't. But shouldn't it be obvious?

Labels:

dissent,

economy,

law,

New York government,

political discourse,

rule of law

Sunday, December 2, 2012

Perspective: Americans Should be Thankful

The United States is not governed well at the moment. Squabbles over the "fiscal cliff," which real adults would have resolved months ago, reflect a loss of perspective and a lack of true leadership.

But at least we are not Russia.

I recently finished Masha Gessen's The Man Without a Face, a biography of Vladimir Putin, in which Gessen describes the cold-blooded brutality of the Russian president's rise to power. She focuses primarily the effect of this one man's character on Russian political culture, but in the background we see the complicity of many Russians themselves. Gessen and thousands of other Russians try to stand up to the lawlessness of their own government, and those dissenters are to be commended. But too may others -- a critical mass, it would seem -- not only condone the nastiness, but act to support it in quiet but equally callous ways. It takes a nation to allow this stuff.

Putin's new program, typical of tyrants everywhere, and totalitarian leaders especially, is to deny his own failure of governance and to fall back on propaganda to pump up support. He wants Russians to be patriotic, so he's putting together slogans and flags and other nonsense.

At least American leaders accept the basic principle of the rule of law. The GOP accepted defeat in recent elections, and did not attempt to steal the vote in the first place. This is no small thing.

But at least we are not Russia.

I recently finished Masha Gessen's The Man Without a Face, a biography of Vladimir Putin, in which Gessen describes the cold-blooded brutality of the Russian president's rise to power. She focuses primarily the effect of this one man's character on Russian political culture, but in the background we see the complicity of many Russians themselves. Gessen and thousands of other Russians try to stand up to the lawlessness of their own government, and those dissenters are to be commended. But too may others -- a critical mass, it would seem -- not only condone the nastiness, but act to support it in quiet but equally callous ways. It takes a nation to allow this stuff.

Putin's new program, typical of tyrants everywhere, and totalitarian leaders especially, is to deny his own failure of governance and to fall back on propaganda to pump up support. He wants Russians to be patriotic, so he's putting together slogans and flags and other nonsense.

At least American leaders accept the basic principle of the rule of law. The GOP accepted defeat in recent elections, and did not attempt to steal the vote in the first place. This is no small thing.

Labels:

dissent,

justice,

law,

paradigm,

political discourse,

rule of law,

Russia

Sunday, November 25, 2012

Another Reason Elections Matter

President Obama has not worked very hard to explain his policy on drone assassinations. By neither denying nor confirming the practice, he has maintained the fiction that they are not really happening; the policy has become one of those open secrets that characterize the worst dictatorships.

image from "The Excavator"

But, as the New York Times reports today, the specter of someone else killing people arbitrarily apparently made the administration uncomfortable enough to take the whole thing more seriously. Scott Shane writes:

This is why regular changes of power are so important. Obama and his people needed to be a little jittery, and they still ought to be even after the election.

image from "Stirring Trouble Internationally"

image from "The Excavator"

But, as the New York Times reports today, the specter of someone else killing people arbitrarily apparently made the administration uncomfortable enough to take the whole thing more seriously. Scott Shane writes:

The attempt to write a formal rule book for targeted killing began last summer after news reports on the drone program, started under President George W. Bush and expanded by Mr. Obama, revealed some details of the president’s role in the shifting procedures for compiling “kill lists” and approving strikes. Though national security officials insist that the process is meticulous and lawful, the president and top aides believe it should be institutionalized, a course of action that seemed particularly urgent when it appeared that Mitt Romney might win the presidency.In other words, having too much power yourself seems like a good idea; giving that much clout to another seems scary.

This is why regular changes of power are so important. Obama and his people needed to be a little jittery, and they still ought to be even after the election.

image from "Stirring Trouble Internationally"

Labels:

dissent,

justice,

law,

Middle East,

paradigm,

political discourse,

rule of law,

UAV

Friday, November 23, 2012

Republican Laggers

If you still don’t understand why the Republican Party

lost the election, here’s some more information:

First, many party functionaries, including Mitt himself,

are angry at New Jersey governor Chris Christie for being overly civil to

President Obama when the president toured areas ravaged by Hurricane Sandy.

People want to know why Christie had to embrace Obama, why he had to fly in

Marine One, why he had to praise the president’s efforts right when the

campaign was coming to a climax.

In other words, GOP-sters can’t understand why the

governor would waste his time governing during a crisis when there was

important work to do in winning an election. What’s the point in expending all

that effort if it does not lead to scoring points in the polls.

This cynical calculation, promoted by jerks like Mitch

McConnell of Tennessee and Karl Rove, lost the election for the Republicans and hamper progress in

serious matters in need of attention from the federal government. Ever since

2000, the Republican Party establishment has operated on the assumption that

getting into office is far more important than doing any good once there, and

people are sick of it. Memories of the political hucksterism and profound

disconnect of the Bush Administration’s response to Katrina (“heckuva job Brownie”) did

as much to cost the election as Christie’s hugs.

Second, Grover Norquist continues to insist that peoplewill refuse to raise taxes at all because that’s what Republicans do, even as

members of the party have finally come around to the position that avoiding fiscal

collapse is more important than electioneering. He is immune to all empirical

evidence, and demands ideological consistency in the face of disaster. Better

to fiddle to the party tune and let the city burn. Even that bastion of socialism, Forbes magazine, has condemned Norquist's tactics as "blackmail" and "extortion," and has labeled him that deadliest of pariahs, a "special interest."

It's time for the GOP to jettison this nonsense and return to efforts to govern the country.

Labels:

dissent,

justice,

law,

paradigm,

political discourse,

rule of law,

tax policy

Sunday, November 11, 2012

What has Changed?

If we are lucky, last week's election will change the political landscape not so much in which policies are adopted, but in the way we talk about government. The Republican Party leadership says it feels chastened, and that its basic approach needs to change. Tea Party attacks, the new statements say, cost the election and led to an embarrassing experience on Tuesday.

Perhaps most heartening is the repudiation of Karl Rove's cynical attempts to manipulate the system. After years of doing nothing but trying to suppress minority voting and issuing Orwellian untruths, Rove has been exposed as a liar and a rogue, who actually needs Fox News anchors to clue him in on reality. His Super PAC's and political gaming failed in this election, when President Obama and the Democrats should have been vulnerable to a whupping.

Now, maybe we can talk about actual policy and engage in meaningful debates. Having lost in every demographic other than aging white men, GOP strategists are suggesting that maybe the party should try something constructive, like passing immigration reform, bagging the Christian-hypocrite position on abortion, and applying sound conservative economic thinking rather than bizarre litmus tests like Grover Norquist's. That kind of thinking would result in a reinvigorated Republican Party, and that could only be good for American politics.

We're not out of the woods, Norquist, Rove and that other cynical stooge, Mitch McConnell, are still trying to defend their old practices. If more progressive and moderate Republicans -- or even conservative ones like Boehner -- succumb to this thinking, we will continue to suffer from political silliness that may prevent serious action on environmental, social and economic issues. The rest of us can't fight this battle; it has to be waged with the party itself, and I am rooting for the good guys, even if I am not a member (of any party.)

Perhaps most heartening is the repudiation of Karl Rove's cynical attempts to manipulate the system. After years of doing nothing but trying to suppress minority voting and issuing Orwellian untruths, Rove has been exposed as a liar and a rogue, who actually needs Fox News anchors to clue him in on reality. His Super PAC's and political gaming failed in this election, when President Obama and the Democrats should have been vulnerable to a whupping.

Now, maybe we can talk about actual policy and engage in meaningful debates. Having lost in every demographic other than aging white men, GOP strategists are suggesting that maybe the party should try something constructive, like passing immigration reform, bagging the Christian-hypocrite position on abortion, and applying sound conservative economic thinking rather than bizarre litmus tests like Grover Norquist's. That kind of thinking would result in a reinvigorated Republican Party, and that could only be good for American politics.

We're not out of the woods, Norquist, Rove and that other cynical stooge, Mitch McConnell, are still trying to defend their old practices. If more progressive and moderate Republicans -- or even conservative ones like Boehner -- succumb to this thinking, we will continue to suffer from political silliness that may prevent serious action on environmental, social and economic issues. The rest of us can't fight this battle; it has to be waged with the party itself, and I am rooting for the good guys, even if I am not a member (of any party.)

Labels:

dissent,

economy,

justice,

law,

paradigm,

political discourse,

rule of law,

tax policy

Wednesday, October 17, 2012

Evaluating Teachers

Teaching in a public school has sometimes been a perilous proposition. In the worst cases, teachers have been subject termination for the content of their instruction, and we might imagine what could happen to a person teaching about evolution in an evangelical district. Only slightly less egregious would be the practice of firing more experienced teachers because new ones are cheaper.

The traditional response to these problems, avidly defended by teachers' unions, has been to offer tenure to teachers with a certain number of years on the job. To an extent, that solution works, in that it de-politicizes the act of teaching and provides some idependence, if not autonomy, for teachers to do their jobs.

Of course, the system also allows incompetent or lazy people to keep their jobs without the concern experienced in almost every other profession about adequate performance. I myself had some terrible teachers, at least one of whom was sleeping with his students, because tenure made it so difficult to move people on. As someone who works at an independent school, I am therefore grateful for the fact that tenure does not apply; we have been able to get people out when we need to do so.

Fairly assessing the actual performance of teachers is not so easy, though. Unlike most other professions, teaching can only be evaluated secondarily; that is, we judge the effectiveness of teachers through the actions of someone else -- the students. Teachers can say with justification that test scores don't accurately measure what they are doing because it is the kids, not the instructor, who must do the job, in the end. Start with students with less talent, with fewer resources, with trouble at home, with inadequate nutrition and you will end with lower scores.

That's why efforts to include classroom visits and other tools in evaluations makes so much sense. Intimidating as these approaches can be, teachers must face accountability for what they actually do. As Education Secretary Arne Duncan noted, “When everyone is treated the same, I can’t think of a more demeaning way of treating people... Far, far too few teachers receive honest feedback on what they’re doing.”

It's time for teachers to see themselves as professionals rather than tradesmen. Standards matter, and we need to help craft and enforce those standards.

The traditional response to these problems, avidly defended by teachers' unions, has been to offer tenure to teachers with a certain number of years on the job. To an extent, that solution works, in that it de-politicizes the act of teaching and provides some idependence, if not autonomy, for teachers to do their jobs.

Of course, the system also allows incompetent or lazy people to keep their jobs without the concern experienced in almost every other profession about adequate performance. I myself had some terrible teachers, at least one of whom was sleeping with his students, because tenure made it so difficult to move people on. As someone who works at an independent school, I am therefore grateful for the fact that tenure does not apply; we have been able to get people out when we need to do so.

Fairly assessing the actual performance of teachers is not so easy, though. Unlike most other professions, teaching can only be evaluated secondarily; that is, we judge the effectiveness of teachers through the actions of someone else -- the students. Teachers can say with justification that test scores don't accurately measure what they are doing because it is the kids, not the instructor, who must do the job, in the end. Start with students with less talent, with fewer resources, with trouble at home, with inadequate nutrition and you will end with lower scores.

That's why efforts to include classroom visits and other tools in evaluations makes so much sense. Intimidating as these approaches can be, teachers must face accountability for what they actually do. As Education Secretary Arne Duncan noted, “When everyone is treated the same, I can’t think of a more demeaning way of treating people... Far, far too few teachers receive honest feedback on what they’re doing.”

It's time for teachers to see themselves as professionals rather than tradesmen. Standards matter, and we need to help craft and enforce those standards.

Labels:

dissent,

justice,

law,

New York government,

teaching

Thursday, October 11, 2012

The Supreme Court and the Rule of Law

In a recent post on SCOTUSblog, Lyle Deniston notes the suspicion of judges held by many members of the Supreme Court. In the oral arguments for Tibbals v. Carter and Ryan v. Gonzalez, attorneys for the states of Ohio and Arizona argued that judges should not be permitted to institute indefinite stays of execution for defendants who are temporarily incompetent to participate in their own appeals. As Deniston points out, the justices were highly skeptical of the practice, largely because they assumed the judges would not be impartial in its implementation. At one point, Densiton refers to Justice Alito 'who suggested that a lot of judges “don’t like the death penalty,” so why should the Court leave to their discretion the issue of stays for incompetency in these death penalty cases?'

This is an alarming attitude for the Court to take, in part because it suggests their assumption they they themselves would be incapable of judicial neutrality when faced with similar problems. Why should we trust judges' discretion? Because their job -- the very name of their job -- requires it. They are there solely to use their discretion. What can it possibly mean for the highest court in the land to say, or even to imply, that we can't trust the judiciary? How can our system, or the very concept of the rule of law, stand up under such skepticism -- or is it cynicism?

This is an alarming attitude for the Court to take, in part because it suggests their assumption they they themselves would be incapable of judicial neutrality when faced with similar problems. Why should we trust judges' discretion? Because their job -- the very name of their job -- requires it. They are there solely to use their discretion. What can it possibly mean for the highest court in the land to say, or even to imply, that we can't trust the judiciary? How can our system, or the very concept of the rule of law, stand up under such skepticism -- or is it cynicism?

Labels:

justice,

law,

political discourse,

rule of law,

Supreme Court

Wednesday, October 3, 2012

The First "Fiscal Conservative"

FA Hayek

Wesleyan University professor Richard Adelstein introduced me to FA Hayek almost twenty years ago, but I had never read his seminal work, The Road to Serfdom until this week. I knew Hayek was the classic conservative economist, who placed his faith in markets and who mistrusted big government planning more than anything. I knew that, through the University of Chicago, he spread his influence such that he was, in some ways, the founder of the American libertarian movement.

I had no idea, however, how lucidly and powerfully he wrote, nor how truly liberal he was. In fact, Hayek used the word "liberal" in the old, 19th-century way -- to mean those opposed to dictatorship and those who believed in the right and the power of the individual to decide his own fate.

For Hayek, the conflict was not between government on one hand and liberty on the other, but between governments that helped facilitate liberty and governments that suppressed it. Mostly, he feared central planning, the effort to make government decide the values -- economic and otherwise -- of all people with goal being perfect efficiency and perfect equality. Planners, he feared, were the first step on the way to totalitarianism because they believed that some rational eye in the sky could decide for everyone what was good and right.

But Hayek was not anti-government. Unlike today's Tea Party types, who eschew all government, Hayek believed it was essential for wealthy societies to provide some minimal quality of life for everyone by funding programs including -- wait for it -- government-sponsored health care. He figured that programs like these only allowed more opportunity for serious individual decision-making. In fact, his second-greatest fear was a drastic difference between rich and poor because it might provoke the kind of thinking that led to Hitler in German and Stalin in the USSR.

I wish the whack-jobs in our political arena could read and understand Hayek, so we could get to the real business at hand and stop wasting our time debating nonsense.

Labels:

dissent,

economy,

justice,

law,

paradigm,

political discourse,

rule of law,

tax policy

Wednesday, September 19, 2012

The "Muhammad Riots" and Essential Values

from allvoices.com

Muslims across Northern Africa rioted last week because they saw an American-made video depicting Muhammad as a homosexual and an idiot. Coming as they do so closely on the heels of the Arab Spring and the recent elections in Egypt, the protests -- many of them violent -- raise serious questions about the clash of values between "Western" and "Islamic" societies.

I have never bought Samuel Huntington's "Clash of Civilizations" thesis, in which he argues that the future of diplomacy will be focus on conflict between essential cultural groups. My problem with his argument is that he provides no useful definition of "civilization," despite his efforts to do so, and therefore can offer no universal rubric as he claims.

But there is no question that the people rioting in Cairo last week do not share American priorities, and Americans do not understand what the protesters are saying as a result. David Kirkpatrick said it best in the Times:

When the protests against an American-made online video mocking the Prophet Muhammad exploded in about 20 countries, the source of the rage was more than just religious sensitivity, political demagogy or resentment of Washington, protesters and their sympathizers here said. It was also a demand that many of them described with the word “freedom,” although in a context very different from the term’s use in the individualistic West: the right of a community, whether Muslim, Christian or Jewish, to be free from grave insult to its identity and values.Many people, when interviewed, simply would not accept the claim that the US government does not ban Holocaust deniers. They assume that every community has the right -- even the obligation -- to ban expression that it finds offensive. The failure to impose such a ban suggests to these Muslims an implicit endorsement of the expression.

We can never resolve this "disconnect." Muslims will not change their views on freedom of expression, and I certainly hope Americans will not change theirs. Both sides have merit, but the American position is, frankly, better.

It is the job of leaders, however, no navigate these differences wisely. Some clashes must result in serious conflict, and some must not. Distinguishing between the two is the essence of statesmanship. So far, President Obama has done well by exerting pressure on Egyptian and other leaders to maintain control while not ratcheting up the rhetoric in a way that will only exacerbate the problem.

Labels:

dissent,

Egypt,

faith,

Islam,

justice,

law,

Middle East,

paradigm,

political discourse,

rule of law

Wednesday, September 12, 2012

What We Ought to be Debating

This cartoon, published at The National Review On-line, represents the crux of our political dispute over the economy.

In the view of conservatives, including (maybe) Mitt Romney, the federal government slows economic growth by restricting the liberty of individuals to adapt and innovate. It also creates dis-incentives for profit, because the government taxes people when they acquire more wealth.

In the Democratic Party view, articulated by President Obama's "you didn't build that" line, government facilitates growth rather than inhibiting it. Building infrastructure, refereeing financial markets and priming the pump all must be done at the federal level, they say, because no other institution has the resources for such big jobs.

The problem is that we are not engaging in debate. Because Romney will provide us with no specific idea of how much government he would tolerate or even endorse, we can't test his assertion that Obama has strangled us.

One reason the Tea Party protester is confused about the government's "hands on Medicare" is because she has not heard any serious exchanges about what that phrase might possible mean. A "debate" in which one side refuses to engage is like the sound of one hand clapping.

Labels:

dissent,

economy,

law,

paradigm,

political discourse,

tax policy

Sunday, September 2, 2012

Do They Even See the Irony?

Also, maybe a little more cash for schools?

Courtesy of "The Dave Factor" : http://davefactor.blogspot.com/2011/08/signs-signs-everywhere-teabagger-sign.html

Courtesy of "The Dave Factor" : http://davefactor.blogspot.com/2011/08/signs-signs-everywhere-teabagger-sign.html

Labels:

dissent,

economy,

justice,

law,

paradigm,

political discourse,

rule of law,

tax policy

Jindal Makes the Case for Obama

Not long ago, Louisiana governor Bobby Jindal was the darling of the Republican Party. Even more recently he won the favor of Tea Party types by refusing to participate in the new federal health care exchanges. He likes to call himself a true conservative, the kind of guy who will keep the government off our collective back.

But when stuff hits the fan on the Gulf Coast, he's more than happy to take some help. In fact, he thinks we all should be backing him up down on the bayou. After Hurricane Isaac hit earlier this week, Jindal said “Protecting the Louisiana coast is good for Louisiana — it’s also good for this country .... It’s a good investment for the country to be making... It’s investing in the goose that’s laying the golden eggs.”

That "investment" took the form of millions of dollars in infrastructure planned, built and paid for the Army Corps of Engineers, the ultimate in federal agencies. The result, Jinda argues, is the growth of important industries, like fishing, in that part of the world. In other words, shrimpers make the money, but they need federal government help to do so. In other words, the federal government has an important role to play in economic growth. Sort of like what President Obama said earlier this summer, when Romney and his ilk mocked the idea.

Guess rugged individual only applies to the other guy.

But when stuff hits the fan on the Gulf Coast, he's more than happy to take some help. In fact, he thinks we all should be backing him up down on the bayou. After Hurricane Isaac hit earlier this week, Jindal said “Protecting the Louisiana coast is good for Louisiana — it’s also good for this country .... It’s a good investment for the country to be making... It’s investing in the goose that’s laying the golden eggs.”

That "investment" took the form of millions of dollars in infrastructure planned, built and paid for the Army Corps of Engineers, the ultimate in federal agencies. The result, Jinda argues, is the growth of important industries, like fishing, in that part of the world. In other words, shrimpers make the money, but they need federal government help to do so. In other words, the federal government has an important role to play in economic growth. Sort of like what President Obama said earlier this summer, when Romney and his ilk mocked the idea.

Guess rugged individual only applies to the other guy.

Labels:

economy,

law,

political discourse,

rule of law,

tax policy

Thursday, August 23, 2012

Monday, August 20, 2012

Bottini Nails the Election

Here's a post from Race Bottini at Off the Bench.

I was doing something else today, but this is much better.

http://offthebenchbaseball.com/2012/08/20/a-baseball-fans-guide-to-the-presidential-election/

The premise: "we’re going to assign each candidate an MLB Manager Equivalent. "

The conclusions: Obama is either Jim Tracy or Kirk Gibson, and Romney is either Bobby Valentine or ... Bobby Valentine.

I was doing something else today, but this is much better.

http://offthebenchbaseball.com/2012/08/20/a-baseball-fans-guide-to-the-presidential-election/

The premise: "we’re going to assign each candidate an MLB Manager Equivalent. "

The conclusions: Obama is either Jim Tracy or Kirk Gibson, and Romney is either Bobby Valentine or ... Bobby Valentine.

Labels:

baseball,

dissent,

economy,

political discourse,

sports,

tax policy

Monday, August 6, 2012

Abdication

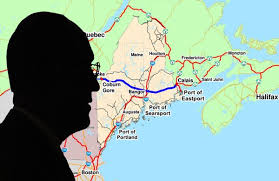

Peter Vigue proposes to build a private toll road across central Maine because “You find that cities, states and the federal government do not have adequate funding to support the demand for infrastructure." He figures that his initial $2 billion investment would turn a profit because freight traffic across the state would be heavy. According to a New York Times article yesterday, "The expansions of the Panama and Suez Canals make this highway even more urgent, [Vigue] said in an interview last week. Bigger ships from around the world, carrying more cargo containers, will be looking for bigger, less congested ports on the East Coast, he said, and Maine already has one in Eastport.

In other words, the environmental and economic well-being of the state is being placed in the hands of a person whose sole motive is personal profit. That's not to denigrate the profit motive. Capitalism depends on the ability to turn a profit, and there are all kids of reasons to think that capitalism works well in many ways. But the ecosystem and economy of a state are held in public trust. We elect officials and representatives to guard our collective interests and to promote "the general welfare." When a state government turns those things over to private interests, it abdicates its fundamental responsibility. "Fiscal conservativism" does not call for such abject failure.

Now is the time to recognize that we must invest in our future. By "we," I do not mean the few very wealthy people with cash to spend. Rather, I mean "we the people," who have invested government with the authority to act. Our constitution is not so toothless, as the Tea Party would have you believe, that it has to fail.

In other words, the environmental and economic well-being of the state is being placed in the hands of a person whose sole motive is personal profit. That's not to denigrate the profit motive. Capitalism depends on the ability to turn a profit, and there are all kids of reasons to think that capitalism works well in many ways. But the ecosystem and economy of a state are held in public trust. We elect officials and representatives to guard our collective interests and to promote "the general welfare." When a state government turns those things over to private interests, it abdicates its fundamental responsibility. "Fiscal conservativism" does not call for such abject failure.

Now is the time to recognize that we must invest in our future. By "we," I do not mean the few very wealthy people with cash to spend. Rather, I mean "we the people," who have invested government with the authority to act. Our constitution is not so toothless, as the Tea Party would have you believe, that it has to fail.

Monday, July 30, 2012

The Personal Side of Drone Attacks

Elisabeth Bumiller, who covers the Pentagon for the New York Times, offered a different perspective on unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) attacks in today's paper. Although the killing that these planes conduct is remote in every sense of the word, the impact on the operators is a lot like hand-to-hand combat.

Bumiller describes the job of an operator in Syracuse, New York, whose "day job" consists of following targets in Afghanistan using UAV's. He will monitor the lives of these people for days or even weeks, waiting for an opportunity to kill them when their families are away. As a result, he gets to know the targets far more intimately than any conventional pilot dropping bombs, and maybe more than anyone other than a spy in deep cover. He follows their routines, watches them care for their children, and then blows them up if he can.

Legally and militarily, this part of the story changes nothing, but it does have serious moral and psychological consequences. The issue is not, in this regard, the morality of the killing itself, but of the system that forces the killers to form such attachments to the targets. The pilot in the Bumiller story said that he had no qualms about what he did, but I wonder what the long-term effect is or will be.

Bumiller describes the job of an operator in Syracuse, New York, whose "day job" consists of following targets in Afghanistan using UAV's. He will monitor the lives of these people for days or even weeks, waiting for an opportunity to kill them when their families are away. As a result, he gets to know the targets far more intimately than any conventional pilot dropping bombs, and maybe more than anyone other than a spy in deep cover. He follows their routines, watches them care for their children, and then blows them up if he can.

Legally and militarily, this part of the story changes nothing, but it does have serious moral and psychological consequences. The issue is not, in this regard, the morality of the killing itself, but of the system that forces the killers to form such attachments to the targets. The pilot in the Bumiller story said that he had no qualms about what he did, but I wonder what the long-term effect is or will be.

Labels:

justice,

law,

Middle East,

New York government,

paradigm,

rule of law,

terrorism,

UAV

Tuesday, July 24, 2012

The Gun Control "Debate"

Here's what the "debate" over guns boils down to, summarized quite nicely in two paragraphs from the New York Times in its initial coverage of recent shooting in Aurora, Colorado:

The "no-compromise gun rights" people like O'Dell believe that more shooting will save lives. He figures that some Coolhand Luke (probably like O'Dell, himself, in his fantasy) would have stood up and calmly put one bullet into the brain of the fully-armored shooter in the movie theater, and then we all would have been safer.

That "radical", Bloomberg, on the other hand (don't you wonder whether O'Dell has any idea who Bloomberg is?), thinks that crossfire is dangerous. He thinks that maybe some cowboy firing back at the original shooter might have done harm.

This is not a debate. It's a bunch of maniacs shouting while rational people talk.

Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg of New York, who has waged a national campaign for stricter gun laws, offered a political challenge. “Maybe it’s time that the two people who want to be president of the United States stand up and tell us what they are going to do about it,” Mr. Bloomberg said during his weekly radio program, “because this is obviously a problem across the country.”Luke O’Dell of the Rocky Mountain Gun Owners, a Colorado group on the other side of the debate over gun control, took a nearly opposite view. “Potentially, if there had been a law-abiding citizen who had been able to carry in the theater, it’s possible the death toll would have been less.The Rocky Mountain Gun Club's website goes even further. It says, "the blatant attempt by New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg to use the blood of these innocents to advance his radical political agenda is disgusting. Mayor Bloomberg’s campaign succeeded in disarming not just these movie-goers, but has created millions of gun-free criminal-safezones across the county.”

The "no-compromise gun rights" people like O'Dell believe that more shooting will save lives. He figures that some Coolhand Luke (probably like O'Dell, himself, in his fantasy) would have stood up and calmly put one bullet into the brain of the fully-armored shooter in the movie theater, and then we all would have been safer.

That "radical", Bloomberg, on the other hand (don't you wonder whether O'Dell has any idea who Bloomberg is?), thinks that crossfire is dangerous. He thinks that maybe some cowboy firing back at the original shooter might have done harm.

This is not a debate. It's a bunch of maniacs shouting while rational people talk.

Labels:

justice,

law,

New York government,

political discourse,

rule of law

Monday, July 16, 2012

Law, Power and the CIA

Henry Crumpton is a paradox: he's a famous spy. When he retired from the Clandestine Service in 1995, the Washington Post identified him as the central subject in at least three major studies of the war on terrorism, so his role was at very least an open secret in Washington DC for some time. After all, if Bob Woodward and the entire staff of the 9/11 Commission knew his name and his game, then there had to be others, too.

By all accounts, including his own in the recently-published The Art of Intelligence, Crumpton brought an innovative and aggressive approach to fighting terrorist groups, especially al-Qaeda. As the head of the effort to find and kill Osama bin Laden in 2002, he combined elite paramilitary troops with CIA operatives to revolutionize the way the United States thought about fighting wars against "non-state actors."

The most important point of his book, in my view, is that intelligence plays an absolutely essential role in foreign policy and security decision-making. Crumpton makes it clear that the most important kind of intelligence comes from human sources -- spies. These people can be contact with foreign governments or diplomats, but the best are "unilateral sources," people recruited by the CIA to provide information. Electronic eavesdropping and overhead surveillance can supplement this HUMINT, as it's called, but only people can select and obtain the kind of up-to-date and significant stuff that leads to good decisions.

Of course, this kind of thing is illegal. The CIA is violating international law by recruiting the sources, and the sources are breaking the laws of their own countries by spying for someone else. Espionage also can include pretty nefarious activity: extortion, bribery, theft, murder. Crumpton wants us to see these facts and confront them. He wants us to accept that fighting bad guys sometimes requires action that would otherwise make us queasy. For the most part, he has me convinced.

But Crumpton misses the other side of that coin. His primary objective is justice. Evil-doers need to be "zeroed out," and he makes no bones about the fact that he believes Jesus wants him to kill them all. I'm not so sure the Gospels support his religious view, and I am certain that the law does not accept his methods. When Crumpton expresses his anger over the fact that the Clinton Administration would not simply shoot a missile at bin Laden because the CIA was almost certain where he was and and was OK withe number of bystanders also likely to be killed, he misses an important part of the government's job: to balance justice and law.

Sometimes the rule of law and justice are incompatible. Revenge may be just but illegal, and spying may be the same way. Crumpton knows, and even says on occasion, that spies should never make policy but only provide information, but he then goes on to describe times when he, as a spy, made policy or complained about the fact that others did not reach conclusions the way a spy would.

Crumpton did his job. I'm thankful his job was not to make more decisions than he did.

By all accounts, including his own in the recently-published The Art of Intelligence, Crumpton brought an innovative and aggressive approach to fighting terrorist groups, especially al-Qaeda. As the head of the effort to find and kill Osama bin Laden in 2002, he combined elite paramilitary troops with CIA operatives to revolutionize the way the United States thought about fighting wars against "non-state actors."

The most important point of his book, in my view, is that intelligence plays an absolutely essential role in foreign policy and security decision-making. Crumpton makes it clear that the most important kind of intelligence comes from human sources -- spies. These people can be contact with foreign governments or diplomats, but the best are "unilateral sources," people recruited by the CIA to provide information. Electronic eavesdropping and overhead surveillance can supplement this HUMINT, as it's called, but only people can select and obtain the kind of up-to-date and significant stuff that leads to good decisions.

Of course, this kind of thing is illegal. The CIA is violating international law by recruiting the sources, and the sources are breaking the laws of their own countries by spying for someone else. Espionage also can include pretty nefarious activity: extortion, bribery, theft, murder. Crumpton wants us to see these facts and confront them. He wants us to accept that fighting bad guys sometimes requires action that would otherwise make us queasy. For the most part, he has me convinced.

But Crumpton misses the other side of that coin. His primary objective is justice. Evil-doers need to be "zeroed out," and he makes no bones about the fact that he believes Jesus wants him to kill them all. I'm not so sure the Gospels support his religious view, and I am certain that the law does not accept his methods. When Crumpton expresses his anger over the fact that the Clinton Administration would not simply shoot a missile at bin Laden because the CIA was almost certain where he was and and was OK withe number of bystanders also likely to be killed, he misses an important part of the government's job: to balance justice and law.

Sometimes the rule of law and justice are incompatible. Revenge may be just but illegal, and spying may be the same way. Crumpton knows, and even says on occasion, that spies should never make policy but only provide information, but he then goes on to describe times when he, as a spy, made policy or complained about the fact that others did not reach conclusions the way a spy would.

Crumpton did his job. I'm thankful his job was not to make more decisions than he did.

Labels:

justice,

law,

New York government,

political discourse,

rule of law,

terrorism

Wednesday, July 11, 2012

"Rule of Law" v. "Rule of the Powerful"

Aristotle wrote that "it is more proper that law should govern than any one of the citizens: upon the same principle, if it is advantageous to place the supreme power in some particular persons, they should be appointed to be only guardians, and the servants of the laws." Hence the phrase "rule of law."

The problem arises when we seek to define the law. Dictators will use the phrase to claim legitimacy. They say "I make the laws, and therefore to abide by the rule of law everyone must do as I say." But such a claim undermines the very purpose of the concept. Aristotle's point -- reiterated and explained by John Locke and Jean Jacques Rousseau among myriad others -- is that LAW exists above and beyond any particular legislators. Majority rule may or may not automatically establish legitimacy, but Congress could no more claim to be the be-all of the LAW than the president could. Generally, the LAW limits power because it requires adherence to a set of principles that dictates what laws are legitimate.

In Egypt these days we have a dispute over this idea. The military junta currently in control complains that newly-elected President Mohamed Morsi has defied the rule of law by calling for the restoration of Parliament. The junta says that they dissolved the Parliament, and they are the law and therefore they rule. The Supreme Constitutional Court agrees with the junta.

Morsi, though he now says he will abide by the ruling of the Court, is correct and the Court and the junta are wrong. In fact, Morsi's actions today only reinforce the idea that he grasps the concept better than the military because he is accepting limits to his own power when he might have recourse to do otherwise.

On this will hinge the future of a democratic Middle East.

The problem arises when we seek to define the law. Dictators will use the phrase to claim legitimacy. They say "I make the laws, and therefore to abide by the rule of law everyone must do as I say." But such a claim undermines the very purpose of the concept. Aristotle's point -- reiterated and explained by John Locke and Jean Jacques Rousseau among myriad others -- is that LAW exists above and beyond any particular legislators. Majority rule may or may not automatically establish legitimacy, but Congress could no more claim to be the be-all of the LAW than the president could. Generally, the LAW limits power because it requires adherence to a set of principles that dictates what laws are legitimate.

In Egypt these days we have a dispute over this idea. The military junta currently in control complains that newly-elected President Mohamed Morsi has defied the rule of law by calling for the restoration of Parliament. The junta says that they dissolved the Parliament, and they are the law and therefore they rule. The Supreme Constitutional Court agrees with the junta.

Morsi, though he now says he will abide by the ruling of the Court, is correct and the Court and the junta are wrong. In fact, Morsi's actions today only reinforce the idea that he grasps the concept better than the military because he is accepting limits to his own power when he might have recourse to do otherwise.

On this will hinge the future of a democratic Middle East.

Labels:

Egypt,

justice,

law,

Middle East,

New York government,

political discourse,

rule of law

Wednesday, June 27, 2012

Egyptian Courts Assert Rule of Law

By denying the power of the army to renew martial law, and Egyptian administrative court today defended a key element of any legitimate government: an independent judiciary. This is very different from the "rule of law" many conservatives -- both here and in Egypt -- talk about, which emphasizes the value of the law in controlling individuals. Here, the courts are attempting to control the government's intrusion into the lives of individuals.

Labels:

dissent,

Egypt,

Islam,

justice,

law,

Middle East,

paradigm,

political discourse,

rule of law

Monday, June 25, 2012

An Islamic Democracy

Hamas won a majority in the Palestinian parliament six years ago now, and at the time it seemed like the first opportunity to test all the claims -- going all the way back to Huntington's "Clash of Civilizations?" -- about whether Islam is or is not compatible with democratic government. That experiment was spoiled, however, by the severe restrictions on Palestinian autonomy imposed by Israel and the United States, sometimes for good reasons and sometimes not.

Elections in Egypt may now give us a new opportunity to see how Islamists rule in a democratic government. But once again, the Islamists and the democrats must overcome un-democratic interventions, this time by the controlling military council of Egypt itself. As Hamas itself has observed, the protests of Tahrir Square have not yet secured victory. We can only hope for more progress in the near future.

Elections in Egypt may now give us a new opportunity to see how Islamists rule in a democratic government. But once again, the Islamists and the democrats must overcome un-democratic interventions, this time by the controlling military council of Egypt itself. As Hamas itself has observed, the protests of Tahrir Square have not yet secured victory. We can only hope for more progress in the near future.

Labels:

dissent,

Egypt,

Islam,

Israel,

justice,

law,

Middle East,

political discourse,

rule of law

Tuesday, June 19, 2012

Bobby Valentine is No Genius

Although every commentator at ESPN save Michael Wilbon thinks Red Sox manager Bobby Valentine is "smarter than everybody else in the room," most of what he does suggests the opposite. His own view seems to be that managing a baseball team well is akin to rocket science -- it's a highly technical matter that only people with large brains can do. He imposes wacky and ineffective "innovations" on his players, like making the first baseman dance around behind a runner instead of holding the guy on in the way that thousands of other coaches and players have determined to be best.

I detest Valentine's attitude, not because I think good managers and coaches are not intelligent, but because the best ones understand that it's not technical intelligence that makes them good. Ron Gardenhire is a great coach because almost every year his teams get better over the course of the summer. His success stems not from creating new ways of playing, but from insisting on sound fundamentals and from earning the trust of his players. Valentine alienates the people he works with by trying to prove all the time how smart he is.

Valentine's most recent foolishness came in the form of a call to have machines call all balls and strikes. As part of his rant against human umpires, he cited a "study" showing that the human eye is incapable of tracking a 90 mph fastball all the way to the plate. I don't know whether Valentine has read the paper or not, but I have. It was written in 1984, by Professor A. Terry Bahill of the University of Arizona, and Valentine does not fairly represent its content. Bahill does indicate that professional baseball players can track a ball much more effectively than most people, and that the eye can not literally track the ball all the way to the bat. To quote:

His point is that the advice to "keep your eye on the ball" is not possible to follow.

But here's the part that Valentine did not know or understand:

Nobody at ESPN appears to have tried to find the source of Valentine's supposed immense knowledge. Valentine does not claim to have done "the study" himself, so why not ask him about it? Did he actually read it? Does he need help understanding it, despite his enormous intellect? Or is he being disingenuous?

Hm.

I detest Valentine's attitude, not because I think good managers and coaches are not intelligent, but because the best ones understand that it's not technical intelligence that makes them good. Ron Gardenhire is a great coach because almost every year his teams get better over the course of the summer. His success stems not from creating new ways of playing, but from insisting on sound fundamentals and from earning the trust of his players. Valentine alienates the people he works with by trying to prove all the time how smart he is.

Valentine's most recent foolishness came in the form of a call to have machines call all balls and strikes. As part of his rant against human umpires, he cited a "study" showing that the human eye is incapable of tracking a 90 mph fastball all the way to the plate. I don't know whether Valentine has read the paper or not, but I have. It was written in 1984, by Professor A. Terry Bahill of the University of Arizona, and Valentine does not fairly represent its content. Bahill does indicate that professional baseball players can track a ball much more effectively than most people, and that the eye can not literally track the ball all the way to the bat. To quote:

Although the professional athlete was better than the students at tracking the simulated fastball, it is clear from our simulations that batters, even professional batters, cannot keep their eyes on the ball. Our professional athlete was able to track the ball u n t i l it was 5.5 ft in front of the plate. This could hardly be improved on; we hypothesize that the best imaginable athlete could not track the ball closer than 5 ft from the plate, at which point it is moving three times faster than the fastest human could track.

His point is that the advice to "keep your eye on the ball" is not possible to follow.

But here's the part that Valentine did not know or understand:

[this data] makes it d i f f i c u l t to account for the widely reported claim that Ted Williams could sometimes see the ball hit his bat. If Ted Williams were indeed able to do this, it could only be possible if he made an anticipatory saccade that put his eye ahead of the ball and then let the ball catch up to his eye. This was the strategy employed by the subject of Figure 5: this batter observed the ball over the first half of its trajectory, predicted where it would be when it crossed the plate, and then made an anticipatory saccade that put his eye ahead of the ball. Using this strategy, the batter could see the ball hit the bat.In other words, the batter (or the umpire) does not need to follow the entire trajectory of the ball to know where it will end up. People with natural talent and training can anticipate with very high accuracy where the ball will be at the end of the track. And the umpire has an even greater advantage over the batter, in that he has a second to make a decision after the ball has stopped, whereas the batter does not.

Nobody at ESPN appears to have tried to find the source of Valentine's supposed immense knowledge. Valentine does not claim to have done "the study" himself, so why not ask him about it? Did he actually read it? Does he need help understanding it, despite his enormous intellect? Or is he being disingenuous?

Hm.

Tuesday, June 5, 2012

Unemployment and the Public Sector

Today is a big day in Wisconsin, as voters there decide whether to recall Governor Scott Walker for his efforts to break public sector unions in that state. I saw a brief exchange on Facebook between two acquaintances that illustrates the strange logic of Walker's position, and reflects some of the trouble in our current political discourse.

In response to one friend's rooting for Wisconsin voters to "get it done," another wrote "I agree. Show the unions they can't just get rid of a governor for doing what he promised he would do in the election. Unions are bankrupting the state. As they are other states."

So what does this response argue, in effect?

First, it assumes that Wisconsin has a very large budget deficit, and that such a deficit amounts to "bankruptcy." Is that true? Using its traditional methods of counting (discussed here by the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel), Wisconsin did have a fiscal gap of about $3 billion -- that is, in 2011 they paid out more than they took in. But this calculation does not constitute "bankruptcy" the way it might for individuals and private companies. Especially in times of economic downturn, government may face budget shortfalls because tax revenue drops and social service demands increase. This is not bankruptcy, it's fulfilling the responsibility of government, which is to "promote the general welfare," among other things. Government is not a profit-seeking venture.

Second, the Facebook reply contends that unions are responsible for whatever budget problems Wisconsin has. There can be no denying that salaries constitute an enormous percentage of any state budget. People are expensive. And insofar as unions protect the interests of those workers, unions are responsible for raising the cost of government in Wisconsin. If union rules cause a loss of efficiency or result in unnecessary work, then unions might be said to cause a real loss in value in Wisconsin. But it is not the unions that are expensive, it's the services. The Facebook reply is therefore mistaken in an important way.

And herein lies a problem with the nature of our national discourse. Rather than assessing the value of government services, we argue about whether "government" is good at all. Does the GOP want there to be no roads, or police, or schools, or parks, or sewers? Of course not. Does it want the best price for those services? Of course, and the Democrats need to pay attention to such issues and respond to them responsibly.

(By the way, the man who complained about public sector pay on Facebook is a soldier in the US Army. I wonder whether he sees any irony. Does he assume that the need for soldiers is just a lot more obvious than the need for teachers?)

But what about those costs? Let's say government workers lose negotiating power, and then lose health benefits as a result. Who foots that bill? Well, the government does, because people don't stop getting sick when they lose insurance, they just stop getting access to primary care doctors. And then what? They go to the emergency room, which is paid for by the state, unless we say that the ill and injured just have to die ... which might run contrary to the "pro life agenda," in certain ironic ways.

Finally, if we are concerned about unemployment and its effect on the economy, then Walker has it wrong. Cutting state jobs only means that all those workers need to find employment somewhere else, and in a downturn they won't find it easily. So, what happens then? The state has to pick up the cost of having more unemployed people, either by providing benefits or by facing the social and political costs that incur.

In other words, Walker may have some things right. Government may be inefficient, and that waste might make economic recovery slower. But the way he went about talking and acting on that observation was such nonsense that it led not to a solution but to a apolitical distraction like the one today. We have to settle down and say real things to each other if we are going to fix anything.

Labels:

dissent,

economy,

justice,

law,

paradigm,

political discourse,

rule of law,

tax policy

Monday, May 28, 2012

Faith and Accountability

In When God Talks Back, TM Luhrmann describes her study of American "charismatic" evangelical groups. She spent several years embedded as an anthropologist in a few of these communities, and gives a thorough and generally sympathetic view of them in the book. Her sympathy, such as it is, stems not so much from shared beliefs, but from her scrupulous efforts at scholarly neutrality -- a product, as she reminds us time and again, of her training as an anthropologist.

Over the course of my own life, I have become ever more firmly atheist as I think more carefully about the meaning of a belief in God in the sense usually meant by "religion." My work as an undergraduate focused in part on the nature of religious belief (specifically in early Mormons) and I am not fool enough to claim any certainty on the question of what God is or is not. Religious faith, like all matters of conscience, can not be disputed objectively, and therefore all serious systems of belief must be afforded a high degree of respect and deference. God does not talk to me, and I don't honestly believe that he talks to anybody (not the least because I don't think anything as large as God could be gender-specific) but I am more than willing to listen to people who say they can converse with the deity. I am very much interested in what they mean by the claim and what consequence they think it has.

And therein lies the rub. Luhrmann tells several stories about congregants who abdicate all responsibility for the consequences for their beliefs. Near the end of the book she offers an account of an exchange between several women in a prayer group. One woman says her daughter refused to wear "floaties" while swimming because "if I had gone down to the bottom of the pool God would have whispered in your heart and told you I was down there." [p.331] The mother and some her friends then laugh, and one even says "I would have said 'Honey, I know this God. You wear those floaties.'" But one member of the group was offended and suggested "we all ought to believe in God like that little girl." In another story a woman refuses to move out of an apartment she can't afford or take a job she does not like because she believes God wants her to be entirely dependent on him. In other words, God is a sadistic enabler.

That kind of stuff bothers me because it leads to irresponsible behavior. Believe what you want, but don't think that it absolves you of all accountability in my eyes or in anyone else's. Only the self-involved and self-indulgent can find a way to justify a staunch faith in God's desire to let them off the hook. Even Muhammad said "trust in God and tether your camel." And if the true believer goes to Congress and argues that we should not worry about climate change because God will take care of it and/or we ant the apocalypse, then his self-involved faith interferes with my efforts to clean up a mess.

Over the course of my own life, I have become ever more firmly atheist as I think more carefully about the meaning of a belief in God in the sense usually meant by "religion." My work as an undergraduate focused in part on the nature of religious belief (specifically in early Mormons) and I am not fool enough to claim any certainty on the question of what God is or is not. Religious faith, like all matters of conscience, can not be disputed objectively, and therefore all serious systems of belief must be afforded a high degree of respect and deference. God does not talk to me, and I don't honestly believe that he talks to anybody (not the least because I don't think anything as large as God could be gender-specific) but I am more than willing to listen to people who say they can converse with the deity. I am very much interested in what they mean by the claim and what consequence they think it has.

And therein lies the rub. Luhrmann tells several stories about congregants who abdicate all responsibility for the consequences for their beliefs. Near the end of the book she offers an account of an exchange between several women in a prayer group. One woman says her daughter refused to wear "floaties" while swimming because "if I had gone down to the bottom of the pool God would have whispered in your heart and told you I was down there." [p.331] The mother and some her friends then laugh, and one even says "I would have said 'Honey, I know this God. You wear those floaties.'" But one member of the group was offended and suggested "we all ought to believe in God like that little girl." In another story a woman refuses to move out of an apartment she can't afford or take a job she does not like because she believes God wants her to be entirely dependent on him. In other words, God is a sadistic enabler.

That kind of stuff bothers me because it leads to irresponsible behavior. Believe what you want, but don't think that it absolves you of all accountability in my eyes or in anyone else's. Only the self-involved and self-indulgent can find a way to justify a staunch faith in God's desire to let them off the hook. Even Muhammad said "trust in God and tether your camel." And if the true believer goes to Congress and argues that we should not worry about climate change because God will take care of it and/or we ant the apocalypse, then his self-involved faith interferes with my efforts to clean up a mess.

Labels:

dissent,

faith,

paradigm,

political discourse,

rule of law

Saturday, May 12, 2012

Drones Come Home

In April of 2011, I posted a comment here on the implications and consequences of drone warfare. My basic concern was (and is) that targeted killings represent a drift from the rule of law. The United States arrogates to itself the authority to identify wrong-doers and to kill them without any transparent or even vaguely public process. Such actions may seem fine when the targets are foreign evil-doers in the "war on terror," but they still indicate a certain attitude about law and the use of force that troubles me.

In the latest New Yorker, Nick Paumgarten describes the ways in which drone technology is moving into the civilian sphere. "Police tend to have a fetish for military gear," he says, "which the purveyors of [drone aircraft] seem to recognize." Though most drones are too expensive for most law enforcement budgets, cops (and others) relish the prospect of using eyes in the sky to find and capture bad guys just like their buddies in Pakistan do. "Still," Paumgarten notes,

In other words, drones don't have to do bad stuff. Like guns, they are tools to be used by moral creatures, as Paumgarten points out.

But that, precisely, is the problem. If our moral and political framework comes to embrace the unilateral killing of bad guys -- if we are no longer governed by a strict sense of the value of the rule of law -- we are far more likely to behave in ways I don't like. The fact that we have shrugged off drone use overseas indicates that we are inclined to accept it elsewhere. I am not reassured that hovering clouds of bee-like drones are not likely to come into existence for a long time because the technology is too far off.

I'm not worried about the machines. I'm worried about us.

In the latest New Yorker, Nick Paumgarten describes the ways in which drone technology is moving into the civilian sphere. "Police tend to have a fetish for military gear," he says, "which the purveyors of [drone aircraft] seem to recognize." Though most drones are too expensive for most law enforcement budgets, cops (and others) relish the prospect of using eyes in the sky to find and capture bad guys just like their buddies in Pakistan do. "Still," Paumgarten notes,

military innovation usually assimilates itself into civilian life with an emphasis on benign applications. The public proposition, at least at this point, is not that drones will subjugate or assassinate unwitting citizens but that they will conduct search-and rescue operations, fight fires, catch bad guys, inspect pipelines, spray crops, count nesting cranes and measure weather data and algae growth... Of course, they are especially well suited, and heretofore been most frequently deployed, for surveillance.

In other words, drones don't have to do bad stuff. Like guns, they are tools to be used by moral creatures, as Paumgarten points out.

But that, precisely, is the problem. If our moral and political framework comes to embrace the unilateral killing of bad guys -- if we are no longer governed by a strict sense of the value of the rule of law -- we are far more likely to behave in ways I don't like. The fact that we have shrugged off drone use overseas indicates that we are inclined to accept it elsewhere. I am not reassured that hovering clouds of bee-like drones are not likely to come into existence for a long time because the technology is too far off.

I'm not worried about the machines. I'm worried about us.

Labels:

dissent,

justice,

law,

Middle East,

political discourse,

rule of law,

Supreme Court,

terrorism,

UAV

Friday, May 4, 2012

Our Descent into Orwellian Language

On April 1, President Obama remarked that a Supreme Court decision striking down the health care law would be "judicial activism" because it would be "an unprecedented, extraordinary step of overturning a law that was passed by a strong majority of a democratically-elected congress."

The blogosphere exploded. As one nut-job yelled, "In his latest display of his full USA federal government dictatorship over both the American people and the former co-branches of government, Dictator Obama is warning the Supreme Court to either rule in his favor or face severe consequences." Never mind that the "consequences" this "dictator" referred to were electoral -- that's far too complex for people of this guy's intelligence level. Fox News commentators fueled the flame, of course, so people with no credentials at all could quote a powerful (but of course never "main stream") news source.

The blogosphere exploded. As one nut-job yelled, "In his latest display of his full USA federal government dictatorship over both the American people and the former co-branches of government, Dictator Obama is warning the Supreme Court to either rule in his favor or face severe consequences." Never mind that the "consequences" this "dictator" referred to were electoral -- that's far too complex for people of this guy's intelligence level. Fox News commentators fueled the flame, of course, so people with no credentials at all could quote a powerful (but of course never "main stream") news source.

But just 7 weeks earlier, Mitt Romney and Newt Gingrich, who I assume, have no aspirations to be "dictator," excoriated the Federal Appellate Court decision on Proposition 8. "Today, unelected judges cast aside the will of the people of California who voted to protect traditional marriage," said Romney. Gingrich went further: "With today's decision on marriage by the Ninth Circuit, and the likely appeal to the Supreme Court, more and more Americans are being exposed to the radical overreach of federal judges and their continued assault on the Judeo-Christian foundations of the United States."

So why is it that when Republicans point out judicial activism they are guarding our liberties but when Obama does it he is tyrannical? Because the Republican Party and its mouthpieces have lost all sense of rational discourse.

And the result? Faith in the legitimacy of the Supreme Court has declined (as I said it would in my last post.) This is a bad state.

Everybody needs to start talking more sanely, but by that I am really calling on Republicans, who have gone off the reservation.

Labels:

justice,

law,

political discourse,

rule of law,

Supreme Court

Sunday, April 22, 2012

What the Supreme Court Must Do

I am inclined to believe that the federal health care law, including the "individual mandate," is constitutional. I can't see how it "fundamentally changes the relationship between individuals and the government," as Justice Kennedy suggested in a question from the bench during oral arguments. It seems like another regulation to me, and one that the government can impose under the commerce clause. The Court ought to rule in its favor.

But the Court must rule unanimously or almost so. This is the real test of Chief Justice Roberts' tenure, and I hope he knows it. Whether the law passes constitutional muster or not may make the difference in President Obama's term, but it probably will not affect the presidency as an institution. If Americans (like me) see yet another 5-4 decision, with the justice split along apparent partisan lines, however, the Supreme Court will be further damaged for the long term.

Especially after the particularly ridiculous decision in Bush v. Gore, in which no justice followed the principle he or she had articulated through the rest of his or her career, the Court has appeared no more disinterested or neutral than any of the other horribly divided political institutions in this country. Roberts must lead here, not as a partisan, but as a Chief Justice. He must find consensus.

But the Court must rule unanimously or almost so. This is the real test of Chief Justice Roberts' tenure, and I hope he knows it. Whether the law passes constitutional muster or not may make the difference in President Obama's term, but it probably will not affect the presidency as an institution. If Americans (like me) see yet another 5-4 decision, with the justice split along apparent partisan lines, however, the Supreme Court will be further damaged for the long term.

Especially after the particularly ridiculous decision in Bush v. Gore, in which no justice followed the principle he or she had articulated through the rest of his or her career, the Court has appeared no more disinterested or neutral than any of the other horribly divided political institutions in this country. Roberts must lead here, not as a partisan, but as a Chief Justice. He must find consensus.

Labels:

economy,

justice,

law,

political discourse,

rule of law,

Supreme Court

Friday, April 13, 2012

Public Transportation and Good Government

Generally speaking, Republicans are not in favor of public transportation. It's expensive, takes a long time to pay for, provides more economic benefits for sectors that support Democrats (like union workers) than support the GOP. New Jersey's Governor Christ Christie is not an exception to this rule, and made his name in part by nixing a major cross-river tunnel to New York in 2010. His argument at the time -- one he stands behind -- is that New Jersey was responsible for far more than its share of the costs.

Yesterday the Government Accountability Office issued a report on that decision which found that many of Christie's claims about the cost of the project were exaggerated, if not entirely false. Democrats, of course, have jumped on the report as evidence of Republican malfeasance. Paul Krugman joined that band wagon in today's New York Times with an op-ed called "Cannibalizing the Future." The Times editorial board added a comment of their own in the same edition.